OMERO.server overview¶

OMERO sequence narrative¶

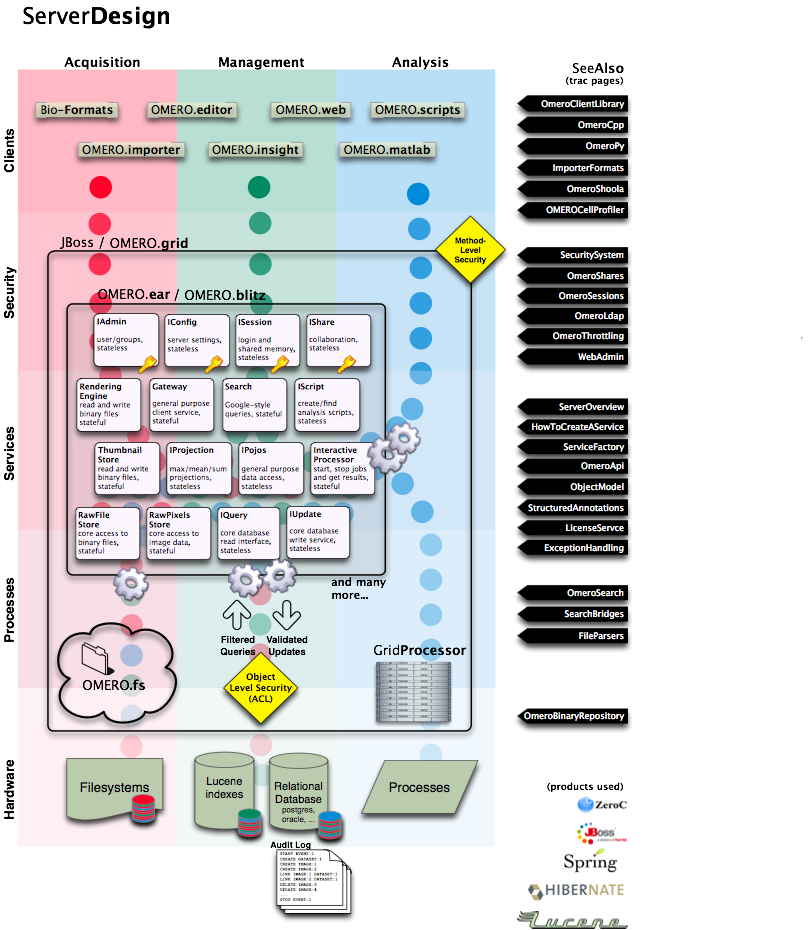

Trying to understand all of what goes on with the server can be a bit complicated. This short narrative tries to touch on the most critical aspects.

A request reaches the server over one of the two remoting protocols: RMI or ICE. First, the Principal is examined for a valid session which was created via ISession.createSession(String username, String password).

These values are checked against the

experimenter,experimentergroupandpasswordtables. A valid login consists of a user name which is to be found in theomenamecolumn ofexperimenter. This row fromexperimentermust also be contained in the “user” experimenter group which is done via the mapping tablegroupexperimentermap(see this SQL template for howrootand the intial groups are setup).If the server is configured for LDAP Authentication, an

Experimentermay be created when ISessions attempts to check the password viaIAdmin.checkPassword().If authentication occurs, the request is passed to an EJB3 interceptor which checks whether or not the authenticated user is authorized for that service method. Methods are labelled either

@RolesAllowed("user"),@RolesAllowed("system"), or@PermitAll. All users are a member of “user”, but only administrators will be able to run “system” methods.If authorization occurs, the request finally reaches a container-managed stateful or stateless service The service will prepare the OMERO runtime for the particular user – checking method parameters, creating a new event, initializing the security system, etc. – and pass execution onto the method implementation. This is done using references acquired (or injected) from the Spring application context.

The actual service implementation (from ome.logic or ome.services) will be either read-only (IQuery-based) or a read-write (IUpdate-based).

In the case of a read-only action, the implementation asks the database layer for the needed object graph, transforms them where necessary, and returns the values to the remoting subsystem. On the client-side, the returned graph can be mapped to an internal model via the ((OMERO Model Mapping|model wrapper)).

In the case of a read-write action, the change to the database is first passed to a validation layer for extensive checking. Then the graph is passed to the database layer which prepares the SQL, including an audit trail of the changes made to the database.

After execution, the OMERO runtime is reset, the method call is logged, and either the successful results are returned or an exception is thrown.

Technologies¶

It is fairly easy to work with the server without understanding all of its layers. The API is clearly outlined in the ome.api package and the client proxies work almost as if the calls were being made from within the same virtual machine. The only current caveat is that objects returned between two different calls will not be referentially (i.e. obj1 == obj2) equivalent. We are working on removing this restriction.

To understand the full technology stack, however, there are several concepts which are of importance:

A layered architecture ensures that components only “talk to” the minimum necessary number of other components. This reduces the complexity of the entire system. Ensuring a loose-coupling of various components is facilitated by dependency injection. Dependency injection is the process of allowing a managing component to place a needed resource in a component’s hand. Code for lookup or creation of resources, in turn, is unneeded, and explicit implementation details do not need to be hard-coded.

Object-relational mapping (ORM) is the process of mapping relational tables to object-oriented classes. Currently OMERO uses Hibernate to provide this functionality. ORM allows the developer to work in a known environment, here the type-safe world of Java, rather than writing difficult to debug sql.

Aspect-oriented programming, a somewhat new and misunderstood technology, is perhaps the last technology which should be mentioned. Various pieces of code (“aspects”) are inserted at various moments (“joinpoints”) of execution. Collecting logic into aspects, whether logging, transactions, security etc., also reduces the overall complexity of the code.